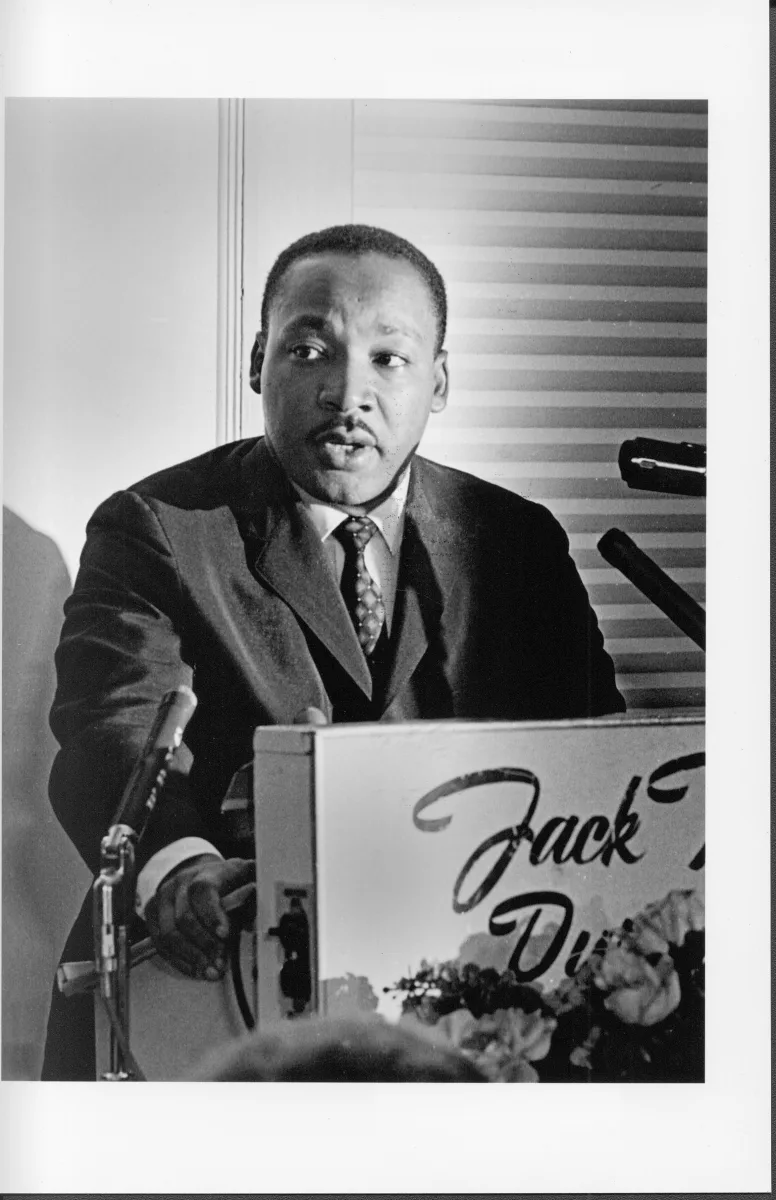

Martin Luther King, Jr., addresses the Southern Political Science Association at Durham's Jack Tar Hotel in November 1964. (Photo via Durham County Library)

NC was a hotspot for hate in King’s lifetime. But it was also the home of civil rights pioneers. So Martin Luther King Jr. was often here.

Martin Luther King Jr. was killed 14 years before I was born, but like most children of the South, I knew about him before I could tie my own shoes.

I knew his face, some of his words, his widowed wife, and, of course, his holiday, which is today. At first, I knew it because it meant we got out of school, then because it seemed to make some people emotional. Some of our grandparents and parents groused about him getting a holiday. Some of them still do.

One of our senators, Jesse Helms, held up official recognition of the holiday. Helms is gone now. King’s holiday isn’t.

King’s death was a seismic event in American history. His life was even more important. And it looms large not just for Black Americans. He’s a giant because you can extrapolate his message to anyone who’s been kicked or held down, anyone who couldn’t afford their light bill or went to the “poor school” or had their rights put to a vote.

He’s thought of as a speaker because his words were so good. But his life showed him to be a good listener too, able to adapt to the labor movement, to changing presidents, to Black Americans who wanted more direct action, and to hate groups that didn’t march in daylight like him but absconded at night underneath bedsheets.

In his lifetime, those hate groups called North Carolina home as much as any other state in the country. Which is why it’s fitting King’s travels took him all over NC, from coast to mountaintop and back again. He always seemed to walk tallest where he wasn’t supposed to.

This MLK Day, we wanted to talk about a few of the places he visited in NC during his life. (For more on MLK’s numerous visits to NC, go here.)

Happy MLK Day. Celebrate it accordingly, not by thinking about him as a statue or a street name or as the reason we get a day off. Don’t confuse pacifism with passivity. Think about him as an active agitator for change.

“True peace is not merely the absence of tension,” he once said. “It is the presence of justice.”

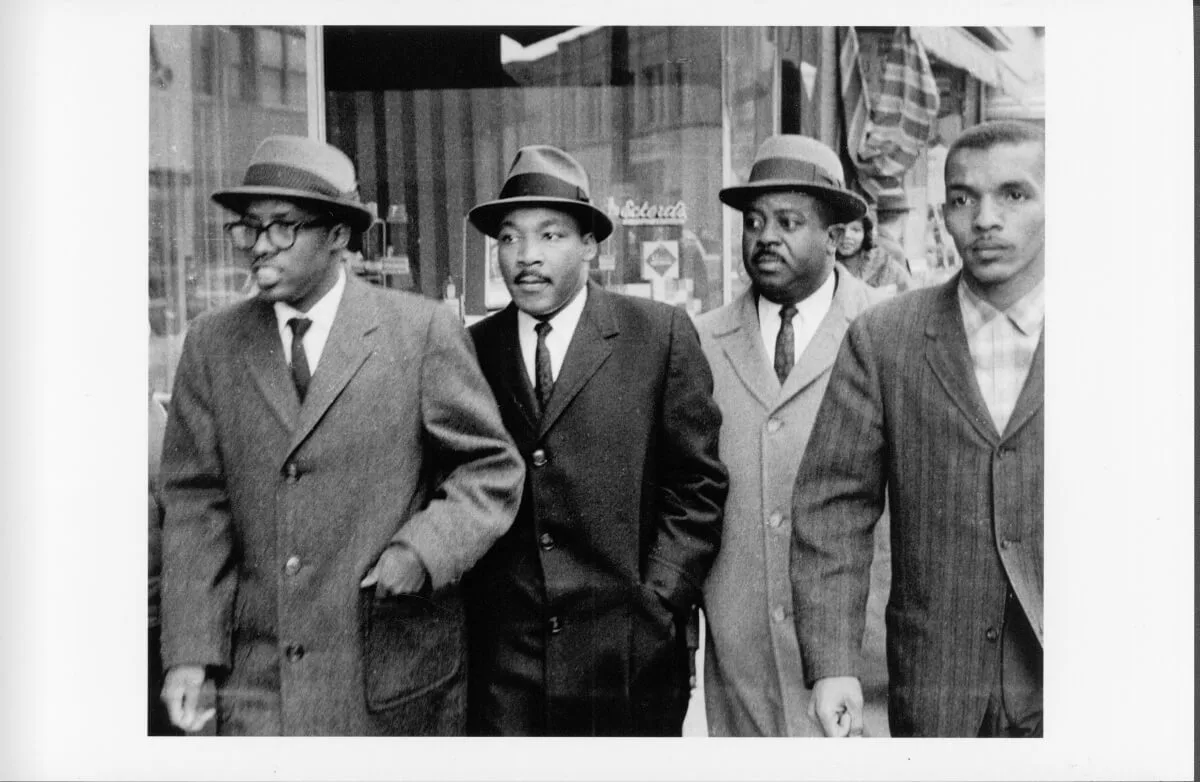

Martin Luther King, Jr., center, visits the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Durham, February 1960. The store had closed the counter after sit-in demonstrations there the previous week. With King are civil rights activist Rev. Ralph Abernathy at left; Rev. Douglas Moore, who led Durham’s first sit-in, in 1957 at the Royal Ice Cream Company, right of King; and an unidentified man at far right. (Photo via Durham County Library. Photographer: Jim Thornton, Durham Herald Sun.

Greensboro (1958)

One of his most significant speeches in NC was at Bennett College, a private, historically Black college for women in Greensboro.

City leaders didn’t want him there but the college did. Wherever there were big moments in racial justice in the South, an HBCU was down the street. King’s “Realistic Look at Race Relations,” as he titled his Bennett address, centered on voting.

“I have no political ambitions,” he said. “I don’t think the Republican party is a party full of the almighty God nor is the Democratic party. They both have weaknesses. And I’m not inextricably bound to either party. I’m not concerned about telling you what party to vote for. But what I’m saying is this, that we must gain the ballot and use it wisely.”

Chapel Hill (1960)

King is a pillar of the church. He took his message from a pulpit, but that doesn’t mean the faith leaders of his day recognized him for the giant he was.

In one 1960 visit to Chapel Hill, students asked King to come and speak at a local Baptist church. King was a Baptist preacher, but the mostly white church didn’t want his kind of “controversy” in their sanctuary.

So he spoke in the church’s basement.

Durham (1960)

Durham notched a special place in King’s life. It’s not hard to see why. The Bull City had a Black middle class to speak of, something denied to Black Southerners in most places.

It also had a strong faith community, and a local HBCU that churned out civil rights icons. One of King’s trips to Durham came amid the Woolworth’s sit-ins, which had begun days earlier in Greensboro.

“Let us not fear going to jail if the officials threaten to arrest us for standing up for our rights,” King told a local church. “Maybe it will take this willingness to stay in jail to arouse the dozing conscience of our nation.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to Durham in February 1960, two weeks after the Greensboro sit-ins launched a transformative new protest movement for young Black Americans. (Image via Durham County Public Library)

Rocky Mount (1962)

Eastern NC is where you find NC’s “Black belt,” the rural counties where descendants of formerly enslaved people still live.

So it meant something every time King went east, and his trip to a high school gymnasium in Rocky Mount is one of the most epic.

There, King delivered an early version of the “I have a dream” speech that should be carved into Mt. Rushmore.

@cardinalandpine ✊🏾 61 years ago this week, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered an early version of his “I Have a Dream” speech in Rocky Mount, NC. He spoke at Booker T. Washington High School in Nash County before about 2,000 people, taking on things like racism and civil and economic justice. Some of the words ended up in later, more publicized speeches like his August 1963 “Dream” speech in Washington, D.C. For more on this historic moment in NC, click the 🔗 in bio! (Audio via Prof. W. Jason Miller at NC State University) #rockymount #nc #martinlutherkingjr #mlkjr #ihaveadreamspeech #northcarolina #history #MLK #martinlutherkingjr #Ihaveadream #todayinhistory #nchistory #ncfacts

Black Mountain (1964)

Western NC didn’t get a lot of recorded visits from MLK. But his 1964 visit to Black Mountain stands astride an enormous moment in American history.

His trip to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in January 1964 was at a time of transition in the Civil Rights Movement. John F. Kennedy Jr., one of America’s more moderate white voices on race, was dead.

Six months later, King coaxed President Lyndon Johnson into the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a groundbreaking moment for racial justice in America.

That year, King went from an idealist to change-maker. That act forever altered the way we think about government’s role in racial justice even today.

Support Our Cause

Thank you for taking the time to read our work. Before you go, we hope you'll consider supporting our values-driven journalism, which has always strived to make clear what's really at stake for North Carolinians and our future.

Since day one, our goal here at Cardinal & Pine has always been to empower people across the state with fact-based news and information. We believe that when people are armed with knowledge about what's happening in their local, state, and federal governments—including who is working on their behalf and who is actively trying to block efforts aimed at improving the daily lives of North Carolina families—they will be inspired to become civically engaged.

Blue Ridge Parkway: Which Helene-damaged areas might reopen in late summer, early fall?

Heading into the summer season, large sections of the Blue Ridge Parkway's winding path through the mountains of Western North Carolina remain...

Learn about NC Civil War history at these 8 spots

If you want to learn more about NC Civil War history, check out these eight sites across the state. One of the most famous and bloody conflicts in...

North Carolina officials celebrate opening of new Paddy Mountain Park

Paddy Mountain Park is officially open in West Jefferson. Discover North Carolina's newest outdoor destination born from community collaboration and...

Opinion: The unfulfilled promises of George Floyd’s legacy

This column is syndicated by Beacon Media and is available to republish for free on all platforms under Beacon Media’s guidelines. The gym’s...